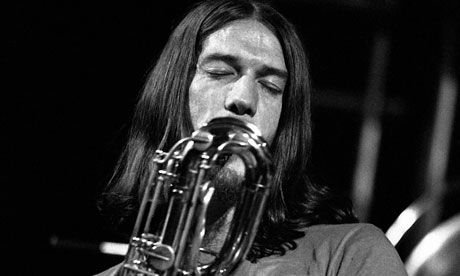

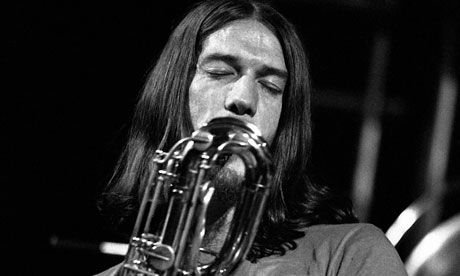

Jim Sherwood obituary | Music | The Guardian: “Jim Sherwood on tour in Germany with the Mothers of Invention in 1967. His principal contributions came on baritone and/or tenor saxophone, though he could also be heard on percussion and vocals. Photograph: Petra Niemeier/K&K/Redferns

Jim “Motorhead” Sherwood, who has died aged 69, was a member of Frank Zappa’s original Mothers of Invention. He appeared on all the group’s early albums, up to and including Weasels Ripped My Flesh (1970), as well as on Zappa’s solo disc Lumpy Gravy. He later performed with the Grandmothers, a group of musicians who had accompanied Zappa during different phases of his career.

Born in Arkansas City, Kansas, Sherwood first met Zappa in 1956 when both of them were attending Antelope Valley high school in California. Sherwood was in the same class as Frank’s brother: “Bobby found out that I collected blues records and he introduced me to Frank, and Frank and I sort of got together and swapped records.”

At the time, Zappa was already in a band called the Blackouts, but this soon disintegrated. Then the brothers moved to Ontario, California, and started a new band, the Omens, which also included Sherwood. He would regularly jam with Zappa in a string of different groups, and eventually, in 1964, the Mothers. The following year, the band signed a recording contract with MGM records, and set about the lengthy process of recording their first album, Freak Out!, with producer Tom Wilson. At the time, Sherwood was not a fully fledged member of the band, which changed its name to the Mothers of Invention. He described his role on Freak Out! as “just making sound effects on some of the songs”.

After the album’s release in June 1966 on MGM’s Verve label, the band went on tour, then in November that year took up a six-month residency at the Garrick theatre in New York, during which they played 14 shows a week. Sherwood was working for the band as equipment manager and roadie, and sometimes operated the lighting during the Garrick shows. These were a bizarre mix of music and performance art, featuring puppet shows and interludes when the band would pelt the audience with fruit.

It was when the Mothers made their first trip to England, in mid-1967, that Sherwood was finally hired as a full-time musician. It was the band’s vocalist and percussionist Ray Collins who gave Sherwood the nickname “Motorhead”, through his love of working on cars and trucks and motorcycles: “He said ‘it sounds like you’ve got a little motor in your head’, so they just called me Motorhead and that seemed to stick.”

Sherwood contributed on baritone and/or tenor saxophone, and sometimes percussion and vocals, to Absolutely Free, We’re Only in It for the Money, and the doo-wop album Cruising with Ruben & the Jets, taking in the Zappa solo album Lumpy Gravy en route. Zappa disbanded the original Mothers of Invention in 1969 for financial reasons and what he perceived as public apathy, but Sherwood appears on the albums Uncle Meat, Burnt Weeny Sandwich and Weasels Ripped My Flesh, recorded before the split but released subsequently.

Sherwood makes an appearance in Zappa’s bizarre and confusing 1971 movie 200 Motels (“Frank wanted me to play a newt rancher and I was supposed to be in love with a vacuum cleaner,” as he put it). In 1973, he played baritone sax on the album For Real!, by Ruben & the Jets. This was a band formed by Ruben Guevara, inspired by Zappa’s album Cruising with Ruben & the Jets, and Zappa played some guitar on their debut album as well as producing it.

Sherwood appeared on the further Zappa releases You Are What You Is (1981), Civilization Phaze III in 1993, the year of Zappa’s death, and the Läther box set, released three years later.

In the 1980s, Sherwood performed with the Grandmothers, and played on a couple of albums with them. During the 1990s, he joined forces with Billy James and his Ant-Bee project.

James, a graduate of Berklee College of Music, Boston, wanted to express his fascination with psychedelic and experimental music from the 1960s, for which he assembled musicians from the Mothers of Invention and Captain Beefheart’s band. Sherwood appears on three Ant-Bee albums, though by this time he had given up playing the saxophone and his contributions are limited to “snorks”, in which you “snort through your nose, sucking air in through your nose”. He added further snorks to Sandro Oliva’s album Who the Fuck Is Sandro Oliva?!? (1995).

“I just feel honoured to have spent time with [Frank Zappa] and the other guys in the early group,” said Sherwood. “[He was] an incredible person, and his music is just something I enjoy listening to all the time.”

• Euclid James Sherwood, musician, born 8 May 1942; died 25 December 2011″

(Via .)